An exploration of the role older adults have played and could play in our communities

Join host Amanda Bostlund around kitchen tables and in communities around Nova Scotia, as she speaks with elders from Mi’kmaw, African Nova Scotian, Acadian and Gaelic communities. This four-episode podcast captures stories and ideas from elders, and about elderhood.

For those of us in Anglo settler communities who have lost the tradition of elderhood, this is an invitation to listen, learn and remember. For all of us, these voices will offer a window into ways of life that are different from our own.

Listen to the podcast trailer

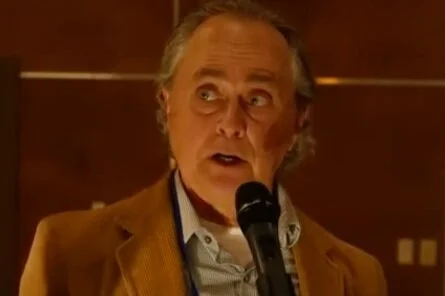

Visit Elder Albert Marshall in his home in Eskasoni

How does someone become an elder in Mi'kmaw communities? What responsibilities does an elder carry, and how are they expressed?

Elder Marshall and his late wife Murdena developed Etuaptmumk, Two-Eyed Seeing, which brings together the best of Indigenous knowledge with the best of Western science. Two-Eyed Seeing is now being applied across many fields internationally. Join Amanda in Elder Albert’s kitchen, as we hear him speak about how thoughtful behaviour can inspire others to live with integrity.

Meet Anna MacKinnon and Emily MacDonald, during a visit to Anna’s home.

The Gaelic Narrative Project reminds us that many of the Gaels among us have maintained a living connection with their ancestral heritage. As a generation of Gaelic-speaking elders or “tradition bearers” is now passing on, the question of what it means to step into this role is very much alive in the community.

During this episode, we meet with two Gaelic women in Inverness County, Cape Breton. Emily MacDonald talks about how her beloved elder Anna MacKinnon takes her back in time and what that means for her understanding of herself and her community. Join Emily, Anna and Amanda in Anna’s cozy home for some stories and songs.

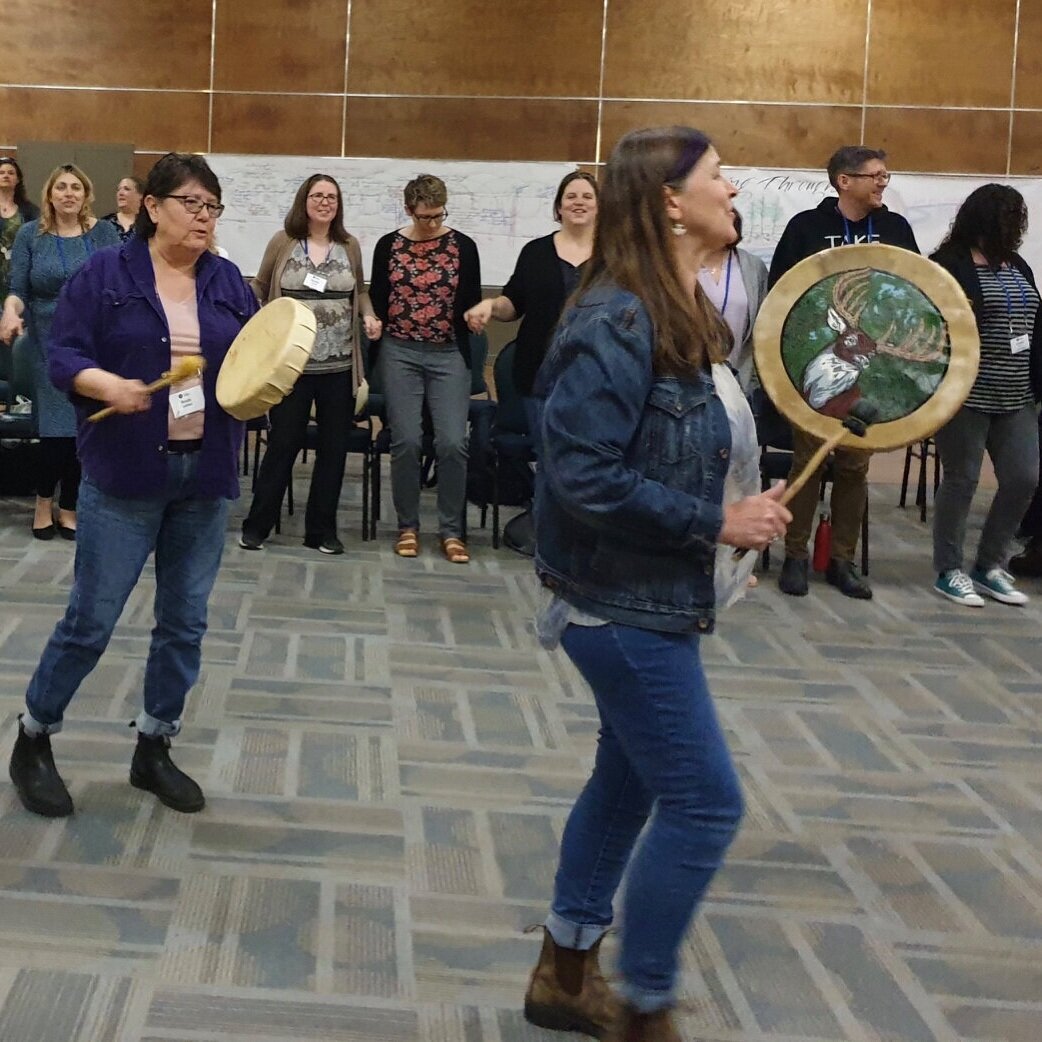

Join Sylvia and Rashida in North End Halifax

What roles do elders fill in their communities? In what less-obvious ways do elders gift youngers with important lessons?

In this episode, two African Nova Scotian women offer a glimpse into the nourishing web of connection and support that foster a sense of belonging in their community. Hear about how people can learn from, and care for, one another throughout their lives, and about strength, patience and kindness. Join Sylvia Parris-Drummond and Rashida Symonds for this conversation with Amanda at the Delmore “Buddy” Daye Learning Institute in Halifax.

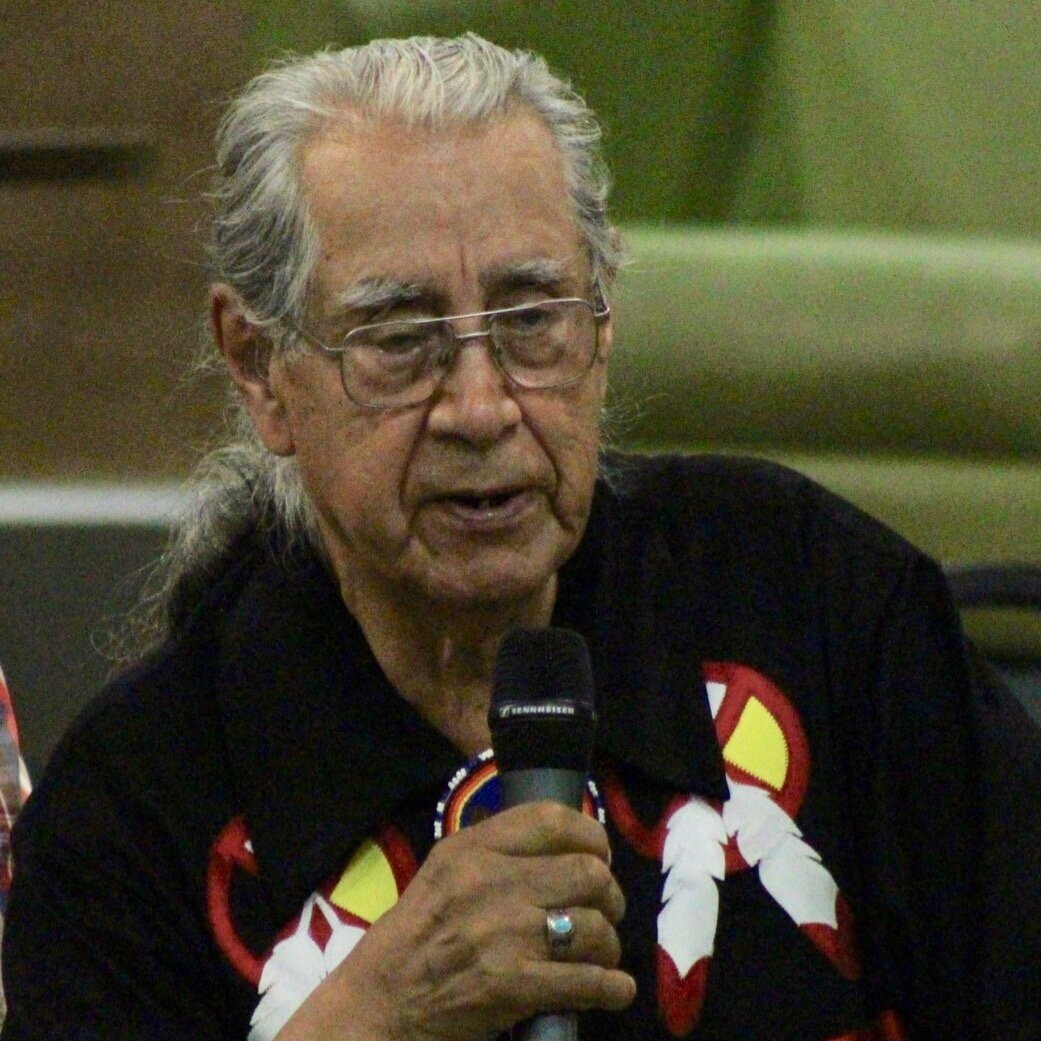

Meet Laurent and friends in West Pubnico

How can learning about the struggles and successes of our ancestors affect us?

How might the knowledge of elders help us understand some of the big issues of our times?

During this episode, we are introduced into the Acadian community in West Pubnico, where most people can easily trace their ancestry back many generations. Meet Laurent D’Entremont as he shares many aspects of his varied past and some lessons he’s learned along the way. Hear also from several women Amanda met at the local museum as they consider questions around elderhood.

Elder Voices was made possible through funding from the Department of Seniors and Long Term Care. It was recorded and produced in Nova Scotia, within Mi’kma’ki, the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi'kmaq.

Tracy George. CEPI Youth connect young people in Cape Breton/Unama’ki with each other and with business opportunities.